What! . . . me, worry?

The problems start even before you're fully awake. There's the fall out of bed that kills thousandss each year. There's the early-morning heart attack, which is 40% more common than those that strike later in the day. There's the fatal plunge down the stairs, the bite of sausage that gets lodged in your throat, the tumble on the slippery sidewalk as you leave the house, the high-speed automotive pinball game that is your daily commute.

Other dangers stalk you all day long. Will a tram's brakes fail when you're in the crosswalk? Will you have a violent reaction to bad food? And what about the risks you carry with you all your life? The father and grandfather who died of coronaries in their 50s probably passed the same cardiac weakness on to you. The tendency to take chances on the highway that has twice landed you in traffic court could just as easily land you in the morgue.

Shadowed by peril as we are, you would think we'd get pretty good at distinguishing the risks likeliest to do us in from the ones that are statistical long shots. But you would be wrong. We agonize over avian flu, which to date has killed precisely no one in the U.S.and Europe, but have to be cajoled into getting vaccinated for the common flu, which contributes to the deaths of 36,000 people each year. We wring our hands over the mad cow pathogen that might be (but almost certainly isn't) in our hamburger and worry far less about the cholesterol that contributes to the heart disease that kills 700,000 of us annually.

We pride ourselves on being the only species that understands the concept of risk, yet we have a confounding habit of worrying about mere possibilities while ignoring probabilities, building barricades against perceived dangers, while leaving ourselves exposed to real ones. Shoppers still look askance at a bag of spinach for fear of E. coli bacteria, while filling their carts with fat-sodden French fries and salt-crusted nachos. We put filters on faucets, install air ionizers in our homes and lather ourselves with antibacterial soap. We used to measure contaminants down to the parts per million,now it's parts per billion.

At the same time, 20% of all adults continue smoke; nearly 20% of drivers and more than 30% of backseat passengers don't use seat belts; two-thirds of us are overweight or obese. We dash across the street against the light and build our homes in disaster-prone areas--and when they're demolished by a storm, we rebuild in the same spot. Sensible calculation of real-world risks is a multidimensional math problem that sometimes seems entirely beyond us. And while it may be true that it's something we'll never do exceptionally well, it's almost certainly something we can learn to do better.

Part of the problem we have with evaluating risk is that we're moving through the modern world with what is, in many respects, a prehistoric brain. We may think we've grown accustomed to living in a predator-free environment, in which most of the dangers of the wild have been driven away or fenced off, but our central nervous system--evolving at a glacial pace--hasn't recieved the message.

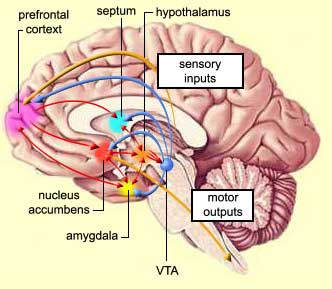

The jumpiest part of the brain--of mouse and man--is the amygdala, a primitive, almond-shaped clump of tissue that sits just above the brainstem. When you spot potential danger--a stick in the grass that may be a snake, a shadow around a corner that could be a mugger--it's the amygdala that reacts the most dramatically, triggering the fight-or-flight reaction that pumps adrenaline and other hormones into your bloodstream.

It's not until a fraction of a second later that the higher regions of the brain get the signal and begin to sort out whether the danger is real. But that fraction of a second causes us to experience the fear far more vividly than we do the rational response--an advantage that doesn't disappear with time. The brain is wired in such a way that nerve signals travel more readily from the amygdala to the upper regions than from the upper regions back down. Setting off your internal alarm is quite easy, but shutting it down takes some doing.

Don't worry . . . I'll continue this tomorrow. I will be very busy today looking for a US bank to buy. It seems the market value of US banks are approaching a level where I can afford one or two.